|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Home

| Synopsis

| Credits

| Calendar of Performances | Critics Speak | Response | Photo Gallery

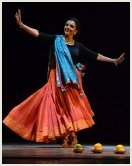

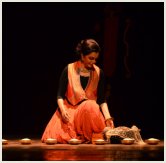

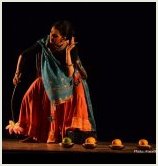

a million SITA-s - Response a Neo Bharatam presentation Response - students' feedback to the performance on May 3, 2015 at the NYU Steinhardt School, Greenwich Village Storytelling in the Classroom, Spring 2015 Dr. Anita Ratnam embodied the epic in her performance of The Ramayana at the Provincetown Playhouse on Sunday, May 3. In a performance that lay at the intersections of theater, dance, music and storytelling, Ratnam and her two musicians explored the ways women have moved history forward throughout the ages. She performed for a packed house full of community members and students across ages and nationalities. The audience was rapt withal, occasionally laughing at an aside or a particularly self aware line about relationships between men and women, but mostly silently taking in the story. I came into the space with some knowledge of the content and with much hype around Dr. Ratnam’s work. I knew there were questions around whether her performance was traditional storytelling. I also entered with my own desire to learn more about Indian mythology and culture. From a visual standpoint, the show was breathtaking; the choreographed movements, colorful fabrics, intricate masks brought the story to life. Ratnam embodied many women in the story, as well as animals (she portrayed a frog with a neat green glove and hand movements) and elements. Interestingly, she did not portray men, and two masks for the main men in the story flanked the stage and framed the action. The moments Dr. Ratnam sang and danced were where she seemed most activated, as if the story was flowing through her and she was merely a vessel for the action. The moments Dr. Ratnam spoke added a layer of removal from the story in a curious way, though I am still processing if that was reflective of her performance or my own perception in the audience. I struggled to follow the story, as there were many characters involved and the plot jumped from backstory to current story. At the end of the performance when Dr. Ratnam spoke more of her process, I was able to understand better. In fact, I found the meta moments that commented on the relationship between story and power to be the most impactful. For example, at one point during the performance, Anita broke character and turned to her musician and asked how many songs she knew about Rama (Sita’s husband) and how many songs she knew about Sita. The discrepancy (dozens for Rama and none for Sita) illuminated the ways that The Ramayana has been filtered through a patriarchal lens to make Rama the protagonist, not Sita. Another powerful moment was when Dr. Ratnam entered the audience at the end of the show and listed the names of “A Million Sitas,” women across time and place and circumstance, as all being tied to this story, one of destiny and agency. Her explanation of the role of the many women in challenging and doing the work of fate clarified and made sense of what had been a confusing performance for me. I also gained much from her explanation of the way this story is (re)told in different ways in India, with three main versions, and that her story was both a descendent from those stories, and also distinctly her own. In many ways, this performance fulfilled my understanding of “classical,” “bardic” storytelling in its telling of universal truths and moments of engaged sharing of myth with the audience. However, the intentional feminist framing and blending of English with Hindi, and the use of costume and prop and infusion of music and dance brought this specific story to life in its particular beauty. Dr. Ratnam’s performance proved the way we humans are, in the words of Erdoes & Ortiz, “connected to the nurturing womb of mythology”, a mythology that links religion, history and nature, a mythology that explains gender, power and destiny, a mythology that makes sense of our world. - Emily Schorr Lesnick Seeing Anita Ratnam tell the story, A Million Sitas was a truly captivating experience. Ratnam combined traditional text and classic storytelling techniques with dance, music, and standard theatrical conventions to bring the story of Sita to life. Coming to the performance of A Million Sitas I was slightly hesitant. This was going to be my first storytelling show and I was skeptical about how the simple telling of a story can keep someone captivated for the full performance. Luckily, I was pleasantly surprised that Ratnam was able to do just that for the entire performance. I think multiple aspects of the show allowed this captivation to occur, such as the “nonconventional” storytelling Ratnam did as well as the audience engagement and energy towards the piece. Ratnam combined the story itself with dance, music, and more common theatrical conventions to create a well-rounded performance. What I loved about her doing this was that it showed different aspects of Indian culture. I felt that I was able to learn so much more than just a story from India, but I learned something about Indian music and Indian dance as well as clothing and masks. I felt I was immersed in the culture by the different aspects of performance that she brought in to share. However, I seemed to have found myself questioning the authenticity of traditional storytelling. With the use of sound effects, costume changes, props, etc., I felt I was focusing on what was happening to enhance the story rather than the story. In addition, parts of the performance with these added theatrical conventions came off as unrehearsed and slightly sloppy, which detracted from the performance for me. I felt that the flow of the story was interrupted, just as if a movie suddenly stopped playing and started again. What was so interesting to me was the audience response during the telling. First of all it was an audience comprised of primarily Indian people and it was so fascinating to see everyone respond whether it be verbally or physically to what Ratnam was sharing. I think it is interesting to see how people react to their culture being displayed so gracefully and respectfully even if it is not a common view just as the story of Sita is in its relation to men of this culture. I felt that the audience really completed the circuit of the performance and that we were extremely valuable to the performance. I realized storytelling performance can be extremely similar to Brechtian theatre. For example, Ratnam told the story, reacted to the story herself and also reacted to the story as a character but not at one time. It seemed that her words were always as a storyteller and her body was a character at times and then her body was herself at other times. In Brechtian theatre, the performer shows themselves as the character, and then steps out as performer and lets the audiences respond, and I feel that was done here as well. It allowed me to react and make my own opinions without being influenced, which I thoroughly enjoyed. Ratnam’s version of storytelling seemed new and what storytelling could be moving towards with the combination of different art forms and theatrical conventions. However, I want to see true, traditional storytelling, “campfire storytelling” if you will, and see what makes classic storytelling so effective without anything extra to enhance it. I think that would be a true, captivating, storytelling, experience that would be great to be part of as an audience member. - Kordell Draper Anita’s Ratman’s telling of A Million Sitas was an engaging and beautiful portrayal of women from Indian folklore. Anita brought the stories of these women alive through costuming, dance, and characterization. Her unique combination of traditional Indian dancing, contextual explanations, and animated acting made for a powerful portrayal that was accessible to all audiences. My previous experiences with Indian storytelling have been through very traditional dance and music. Past performances that I have seen have been done completely in a native Indian language and all danced, with each dance flowing seamlessly to the next. I appreciated that Anita kept some of the traditional elements of this while breaking the dance and songs to tell the story to an English speaking audience. Beyond the actual story, Anita would also break to provide some cultural background and explain how the gods are understood now in the Indian community. There was enough narration and explanation in English for westerners to enter into the Hindu epic, while also maintaining enough traditional elements to appeal to Indian audience members as well. Anita’s unique storytelling was characterized by her use of traditional dance, suggestive costuming, and physical characterization of the women she was representing. Since this epic follows four very distinct women, Anita introduced each character with a unique dance and piece of costuming that highlighted their personalities. After a verbal description of the character, the dance and costuming allowed the audience to really experience who these women were beyond words. The dance set the mood for that portion of the story being told. First, Mandodari, Ravana’s wife, was represented by a green glove depicting her earlier life as a frog. Anita’s facial expressions and movements through the dance were enticing and alluring. Then, Manthara was contrasted with this character by wearing a tattered shawl to show her status. She danced with a basket as a hunchback and made abrupt, swift movements to show her desperation to remove Rama from power. Later, Anita described Ahayla by her immense beauty. Anita used a simple gray cloth to represent her elegant and majestic beauty. However, this simple cloth was regally draped around her waist and shoulder as she danced very gently and graciously to show Ahalya’s angelic character. As Ahalya is cursed by her husband and becomes a stone, the gray fabric is used to cover her and reveal the shame that traps her. Next, Anita almost completely changes costumes to introduce Surpanakha. Her dark flowing pants, witch like fingers, angered facial expressions, and eerie movements help us to know that is a character not to be trusted. Anita helped us to enter into the world of these women through dance, clothing, and expressive movements. The ending of the story helped the audience connect personally and tie the stories of these women together. Anita ended the story about Sita by handing audience members rose petals as she explained how we are all Sita in the way that we share the struggles and adversity of women. Handing us the rose petals helped us to think about how there is a bit of Sita in our own lives. It was a way of connecting the stories of all of this women and inviting us to remember our own as well. The performance made me think of how women are depicted in religious stories that I grew up with. Like Indian culture, women in the Bible are often overshadowed by the dominating male characters. However, when you take the time to really look at their stories, I see strong, very influential women. It was very powerful for me to hold these petals in my hand along with all the other women (and men) in the audience as I thought about the remarkable story of these Indian folktales. The tangible experience of the role petals also was a symbol of giving us the gift of storytelling. It was a beautiful way to leave the audience at the end. Although this was more performative than a lot of the work that we had done in class, it did reflect a lot of what we had talked about and the reading we studied. These stories were used as a way to pass on the history of Indian culture, unite a community of women, and cause the audience to reflect on their own life through the story. - Megan Ibarra It was a distinct pleasure to view the storytelling by Anita Ratnam at Provincetown Playhouse. As a dancer who briefly studied Bharatanatyam in my undergrad and in my years here in New York, I came to this performance with a certain amount of understanding of the inherent connection between storytelling and this specific dance form. Remembering a wonderful storytelling my professor had shared while we were in school – dynamically physicalizing his words with crisp and expressive mudras (hand gestures) – I was curious to see how Anita would blend this dance form with the traditional art of storytelling as we studied it in our course this semester. This was a very ambitious show incorporating props, recorded music, live singers, jewelry and costume changes, talking, instruments, live music, and dancing. The first element that I noticed was Anita’s choice to work in a more upright (pedestrian) body position. Many of East Indian styles incorporate deep bends of the legs, an angular triad of shifted weight in the hips, torso, and head positions with Bharatanatyam being, in my experience, especially grounded, rhythmic, and angular. I found her more fluid style (going from extreme formalized movement, through the natural body of the human storyteller – talking to the audience and responding to them) allowed her to create a show that had so much complexity, both in story and presentation. In researching Anita a bit more through her website (http://www.arangham.com/anita/performr.html), her approach to the performance became clearer. Blending several movement styles and with this idea of striving for more freedom and circular motion, she stated “I have learnt that the expressions of the body are infinite and we need to unlearn some of our training in order to open ourselves up to the entire vocabulary available to us as dancers. In doing so we will not be unfaithful to our source for in tradition is the basis of our cultural DNA and then we can begin to become world citizens in the increasingly exciting world of art." Some of the moments that resonated with me the most were the ones where she took a single element (ex. green glove) and allowed that to identify and transition her from one style of movement to the next. Having the one prop that abstractly identified a character, allowed me as an audience member to not only have access to follow her into the story, but it let me fill in the gaps with my own story and imagination, while carrying me to the essence of the story – the specific frame in the storyboard. At times the multiple props became overwhelming – taking it more into the theatrical element of “acting something out” versus storytelling where I feel there is more space for the listener to be part of the creation. In those moments, I felt like I was missing details and was not given the same permission to trust what I was taking from it. Another element that was very helpful in following the story and the names that are less familiar to those of us in the audience who do not know the language was her use of the masks of the two men – the two characters who became the visual constants, while the women moved around between and behind these men. Her desire to incorporate her personal vocabularies and movement knowledge, allowed her to uniquely present an epic story that has been told, and retold, for centuries. Her focus on the female characters was a refreshing way to view the story of Sita and Rama – offering a through line. I realized again in listening to these stories, that the storyteller’s cultural context still informs and embeds itself into their focus and perspective – specifically in her choice to focus on the women. Not understanding the role of women in that culture in an experiential way, however, I believe that I missed some of the subtlety that the East Indian audience members would have noticed. Often the women were still making choices to place the men and their legacy above themselves no matter what, and I would have appreciated a brief insight (lecture demonstration, article or discussion) on what the traditional role of the women is, and if/how the women in the story were going towards or against that. Perhaps simply acknowledging their story as a story worth telling is a big stance to take. For me to fully know the meaning and purpose behind her choices as a performer – and her artistic expression – I felt I needed a better understanding of her social and cultural environment. Overall, this was a thrilling experience and a story I was so happy to have engaged with in this way. I look forward to following the next storytelling series and can’t wait to engage these new approaches into my classroom. - Meggie Smith A Million Sitas, Including Me Anita Ratnam’s description as an “intersectionist” is an apt and accurate characterization. She brings theatrical spectacle to storytelling with the use of music, props, dance, and costume. What strikes me as the most successful aspect of her performance, which I have seen many one-man “shows” lack, is her easy integration of all of the above. Her costume changes occur right on stage with little to no disguising of them; she speaks frankly to the audience about her purpose, giving life not only to the stories but to the audience as well, and she even speaks to her assistants on stage (Ratnam) – no fourth wall in sight. Her use of props and gestures in dance particularly stand out. She employs various fabrics throughout her storytelling, and she paints such a vivid picture, she can turn those scarves into anything! In particular, her use of a grey scarf to convey the sadness of Ahalya as she turns into stone was haunting. In Ratnam’s dances her sharp gestures do the storytelling for her, and this was especially clear to me in her portrayal of Manthara the hunchback instructing the queen to claim her two boons. I am certain there are many gaps I could not fill when interpreting her dance. This type of storytelling reminds me of Josephine Cho’s Korean storytelling in class – I could not tell what exactly happened, but I understood the message of the value of honesty quite clearly. Ratnam’s woman-centered themes were not lost on me, however, even through dance. Ratnam’s storytelling in another language besides English also created gaps in the story for me. In listening to her singing and chanting I was reminded of our collegial debate in class on the question of “whose story is it?”. Being a non-South Asian and very unfamiliar with The Ramayana, I noticed jokes or references at which South Asian audiences chuckled or murmured, but were lost on me. I understood that this storytelling was a feminist retelling of The Ramayana. Ratnam explicitly shares as much with the audience, though she does so briefly, moving on to making jokes on Rama’s behalf. At first disappointed that there seemed to be a whole world of the story I was missing, by the end of the storytelling, I found I was glad to have heard this version first. After all in listening, “each person creatively reconstructs the story being told through their own imaginative response”. Even if I had heard or read The Ramayana hundreds of times before, Ratnam’s retelling on May 3, 2015 would always have been different to me than anyone else’s reception of it in that audience. My story, reconstructed in my mind out of hers, was confirmed when Ratnam announces she is Sita and so are all of us. I understood her story about Sita to be about the sidelining and silencing of women both in India and around the world, both today and throughout history. Whatever I might have “missed” on that stage did nothing to hinder the impact of “A Million Sitas” for me, another testament to the effects of storytelling. - Melissa Sokolski I was very pleased to have been able to make it to Anita Ratnam’s performance this weekend. I was very eager to see the blending of story and dance, particularly as I know many classical Indian dances are based in story. While I am somewhat familiar with Indian dance, I do not have much experience with Indian stories. However, after hearing Anita, I realized that I have heard pieces of Sita and Rama’s stories in other contexts (usually focused on Rama, as Anita pointed out). In particular, the characters make an appearance in a story in the 1990’s movie version of A Little Princess, which was a staple of my adolescence. I found it interesting to see how Anita opened her story with an informal conversation about the character Sita, and her place in the Indian folk canon. She came back to this informal voice several times, which I found both informative and distracting, which I will come back to. Anita’s presence on the stage is powerful and captivating, and I appreciated her costume and set. I wish that I could see the full show she normally puts on, because I believe that what she did at Provincetown was very ambitious in terms of production, and in some ways detracted from the telling of the story in that particular setting. As a performer, I am often hyper-aware of production elements which don’t necessarily bother other people. In this particular performance the complex costume changes took away from the flow and grace of the storytelling. I appreciated Anita’s need to differentiate the women in the story, because there were so many, and each was unique and important. Which seems to be a main issue with telling an epic: there are so many characters involved! I found myself enthralled with each woman, story and sad that it was so short. I was also struck with the huge cultural learning curve which hearing this story requires. I do not believe that you have to know the culture a story originates from in order to appreciate it (as we saw during our class), but in the case of an epic like the Ramayana there was a lot of literacy I felt distinctly lacking in. If I had grown up in India, hearing little bits and tags of stories about Rama and Sita, having their stories and lessons leak into all the pieces of my own personal history, I would understand them that much better. While I was pondering this I realized that I can use this paradox as a tool in the classroom to help students understand each other better. Just like a story, a person is complex, and if you are unfamiliar with their context then you may not really understand them. Especially in a classroom with students from many cultural backgrounds, it would be so interesting to have each student come in with an ‘epic’ that comes from their country. We can tell these stories and then see the questions that we all have about them. A student may never have considered that someone might not know why Rama was blue (really, why is he blue?), and in explaining this we can discuss how the story we tell on the outside is never the whole story…there’s always so much more to learn. I had mentioned Carmen Deedy and John McCutcheon in my last paper, and I think that one of the reasons I connect with them both as storytellers is that they tell personal stories. Personal stories are different from epics or folk tales because they are teaching us about a person, you don’t really have to know the person first. While listening to Anita tell her epic story, I wished in some ways that it had stayed centered on Sita, that she became Sita and told us ‘her’ story. Each time she stepped out of character to give us some useful information I kind of lost the emotional thread of the story. I loved the parts where I felt Anita become Sita, and the beauty of connecting Sita’s beginning of being found in a furrow with her ending of returning to the furrow was so powerful, that in a way, I didn’t really even need the stories in the middle…and I certainly didn’t need the men! - Paige Horton Anita Ratnam’s storytelling of A Million Sitas (on May 3, 2015) began for me as soon as I walked into the theater space at The Provincetown Playhouse just minutes before the scheduled start of the show. I was seated in the first few rows towards the right side, but easily could see Anita Ratnam as well as the two other performers that were a part of her show to the left of me on the stage. All three of them seemed to be already engaged with themselves, the energy of the room, and readying themselves to engage our imaginations with their story. They had steady poise and focus in their bodies and eyes that was palpable to me. There was immediately a unique synergy that I could feel in the air of the audience that I think is specific to a one-time performance in a given locale. This clearly was not an extended run of a Broadway or off-Broadway full-length play. While there was a traditional theatre essence to it, being at New York University among academics and students with ties to Greenwich Village, it very much had its own unique quality of being a one-time storytelling that we truly had to lend our ears to or risk missing all its glory and magic. One of the highlights of the show for me was actually the beginning in which Anita along with her performing partners guided us in a moment of silence for people in Nepal in light of the recent Earthquake as well as silence for people in Baltimore in light of police brutality affecting the Black communities there. It was a very short moment of silence but the fact that she took even that moment to encourage us to engage with other parts of the country and the world I felt was very powerful and naturally made her someone we truly wanted to listen to; learn from. Who was this woman? What was her artistry that she wanted to show to us? How might her storytelling in the present moment connect to or shed light on Nepal? Baltimore? New York City? Ourselves? Our own histories, past, present, and futures? In our class this semester we discussed briefly how “stories” or “storytelling” has been such a buzzword as of late for people to market, sell, or simply elicit empathy and personal investment for certain campaigns, whether it be business-related campaigns or campaigns for civic rights and social justice. Many nonprofits I have been involved with have used “story” (i.e. “what is your story?”) in connection to the nonprofit’s mission and goals as an agenda strategy for fundraising. Usually companies and nonprofits utilize real stories to get buy-in from real people, but as I sat there thinking about Nepal and Baltimore and seeing the theatricality of “Sita” come to life I couldn’t help but wonder what was Anita’s personal story and what compelled her as an artist and as a person to tell this re-imagined story of “Sita” in the way that she was doing. In other words, why was this important to watch and listen? I feel there is something to be said about a forged connection between the new story of a contemporary culture and an older story that has been told and retold and has evolved throughout many generations of history. When she began her show and then immediately interrupted herself to pause and directly ask someone in the audience to put their handheld phones and recording devices away I felt that she was honoring the art of live theatre and storytelling and doing the audience a service by reminding us that storytelling should be told and received by people coming into face to face contact; that its ephemeral and fleeting nature is what renders it power and prominence throughout generations. And while it is a hard concept for many people living through a social-media dominated American society to accept, it is something we must accept or risk losing that sacred experience forever. Ultimately, in a strange way I felt more connected to Nepal and Baltimore and to the world when I felt that everyone in the room was off their mobile devices and focused on putting their energy into one place to share an experience, even if it was a storytelling from a Hindu epic and not necessarily a newsworthy “true story.” What was most captivating about her show was the graceful and enchanting performance of her storytelling and I am not referring simply to her voice or articulation of the story of “Sita” but what seemed to move me the most was the fluidity and spirit of her movement, connected with rhythm, and connected with the curiosity, allure, and taboo she weaves around the story of the “Sitas” that seems to ultimately render Sita someone beloved rather than scorned or unwanted. The rhythm of her movement as she stomped and danced to the beat of the music and the way she was in sync with her partners on stage situated me in the present to actively listen and lean on the edge of my seat to continue listening, as if sitting on the floor of my living room or around a campfire, rather than stiff in a velvet-lined theater seat. I believe there is something innate in human beings that we easily latch onto the beauty of simple repetitive sounds and movements that are so essential to our enjoyment of our own bodies in space and in spectatorship of other bodies in space. There is something about repetition that builds momentum and engages all as a community. It seemed that once she transfixed me with the sounds and movements of her dance-theatre I was then ready to hear her vocals and words and overall verbal telling of “Sita”, which I saw as just another important aspect of the telling of her story using a certain faculty of her body, rather than the only aspect of storytelling worth recognizing or celebrating. Often in many theatre mediums or traditional theatre settings performers may place too much focus on their intellectual and vocal capacities (as they analyze and critique scripts), easily forgetting the possibilities of one’s body, mind, and soul when it is tied to not only words, but song and dance and music and all that lies in between what may be part of the full range of a human’s capacity for storytelling performance. When Anita detailed how the name “Sita” is not often used as much as other South Asian names it immediately made me feel as though Sita was an outcast and someone waiting to be discovered or valued, which I feel is a feeling that many young girls may identify with not only in America but across the globe. The fact that Sita must constantly prove her chastity shows her vulnerability as a woman tied to a man’s jurisdiction. By the end of her performance we see that Sita is truly a woman to be loved and respected for she has not led an easy life. And although it is not a name that is used often for baby girls, perhaps that is what makes a “Sita” special. And at the same time Anita ended her performance by saying that we were all “Sitas”, echoing the sentiment of the title of her piece that “a million Sitas” do exist. I believe that there is this underlying and often unspoken universality to human nature that lies within every individual that at one point or another we have gone through difficult times in our lives or have felt the pain of others in our hearts, and perhaps it is through these trying experiences that we are all “Sita.” But does living through hardship make one’s life not worth living? Does it make it any less than any other person’s life? I believe that the fine line between the legacy of what makes a blessed life and a life that is full of pain and suffering is what makes Anita Ratnam’s story so fascinatingly complex and yet accessible to all. This show fit with my expectations based on our class in terms of varied storytelling elements that a performer might utilize, but it also exceeded my expectations in the way it captivated my imagination. - Victoria Chau |